Chapter 6: The Place des Nations: A Square in Search of Meaning

This sixth article in the series on the architectural history of international organizations in Geneva considers the urban planning dilemma caused by the building of the Palace of Nations on the Ariana estate. A dilemma that was tackled, but never resolved, by several international architectural competitions occurring over the course of 50 years. A minimalist solution emerged only in 2000, after a final contest.

A 12-metre-tall wooden chair with a broken leg embodies the most recent discord between Geneva and the United Nations. Designed by Daniel Berset for Handicap International, it was placed opposite the entrance to the Palace of Nations, in August 1997, to symbolize the devastation of land mines, which UN member states were working to ban. Once the Ottawa Treaty was signed, in December 1997, the sculpture was to be banished to the graveyard of departed symbols –– or possibly burned in its creator’s fireplace. Its power of seduction had been seriously underestimated, however.

The Genevans, who relished the challenge of its missing leg, and visitors, who love surprises, together forced the city to leave the chair where it was. The UN protested that a broken chair was not a fitting symbol of global governance. But it had no say over a sculpture and a square that belonged to someone else. In 2007, when the monumental plaza promised to the League of Nations in 1929 was finally inaugurated, a sober yet whimsical chair had already taken hold of the square. Tourists snap photos of its imposing silhouette, which looms over the children playing among the water jets. It asks “Why?” and stimulates the imagination. It offers shelter from the sun and rain. Its legal status is tenuous, but it is culturally well integrated.

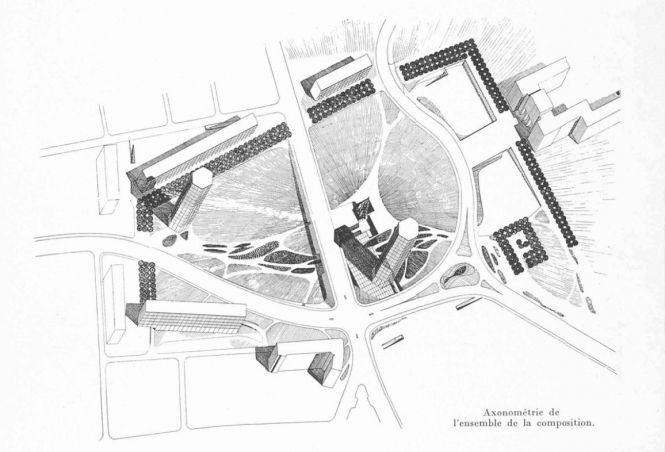

Plan by French urbanist André Gutton, awarded first prize in the competition in 1956

© Bulletin technique de Suisse Romande; volume 83; cahier 15; 20 juillet 1957

Only after a fourth and last architectural competition, in 2000, did the Place des Nations - a constant headache for Geneva’s international quarter since the 1930s - finally acquire the form and purpose it had sought, and failed to achieve, for so many years. Admittedly, the square was a difficult equation to solve. The decision to establish the League on the rather isolated site of the Ariana required new access roads and a suitably attention-grabbing square in front of its Palace. In 1934, two roads were built: the Avenue de la Paix, from Rue de Lausanne to the Ariana, and the Avenue de France, from the lakeside quay to the Ferney–Paris road. The area between the two avenues, facing the Palace, was reserved for the future “Place des Nations”. The square was connected to Cornavin station by Rue de Montbrillant and to the west of the city by the Avenue Giuseppe Motta. The main difficulty in this configuration - four avenues, one located on a major thoroughfare between Italy and France, surrounding an empty plaza with a largely symbolic role –– was to reconcile movement and stillness, traffic and contemplation, cars and pedestrians, beauty and flow.

The first competition, held in 1934, suffered from a double handicap: the League refused to allow any development on its land, and the purpose of the potential buildings around the square was not yet defined. Nonetheless, a first prize was awarded, studies were carried out, an urban plan was drawn up. Conflict soon arose over commercial buildings going up in the Varembé neighbourhood, initiated by local developers without taking into account the overall perspective. A committee of experts, appointed by the League and the Geneva government, ordered the buildings torn down. Regarding the square, however, it agreed that the main priority was to wait. The experts’ report reveals a poorly defined project: what did a “square” mean in this particular spot? An empty space surrounded by buildings? a tree-planted plaza?

The outbreak of World War II put an end to their deliberations. They resumed in 1945, after the United Nations took over the mandate of the League. The economic and political exuberance of the post-war years fuelled ambitious ideas for developing Geneva’s international quarter. The city’s population was growing fast, requiring new services, housing, and schools. The Place des Nations was quickly turning into a busy crossroads, peopled by international civil servants, local residents, tour buses, and motor vehicles en route from the Mont Blanc tunnel to the Faucille Pass over the Jura Mountains. Traffic was smothering the square. In 1955, the local government, aware of its responsibility, along with the UN, which had been anxiously awaiting a solution, announced the brief for a second international competition, in May 1956. One hundred and twenty-three architects took part, including some from Russia and its satellite states.

The ITU pentagonal tower, what remains of the 3 tours envisaged by André Gutton

© Alain Grandchamp / Documentation photographique Ville de Genève

The jury acknowledged the difficulty of “reconciling the creation of a monumental square and the organization of a crossroads with several heterogeneous traffic flows”. They awarded first prize to the French town planner André Gutton, whom they felt had shown the best understanding of the complexities involved. Gutton’s solution was to dilute traffic by spreading it over a larger area to free up the square itself, which was thus “totally given over to pedestrians” (1). The success of his scheme hinged on completing an airport bypass on the future Lausanne–Geneva freeway. Unburdened by traffic, the square would comprise a leafy park with lawns and flowerbeds, overlooked by three glass towers set in a triangle 450 metres apart: “triumphant, pure, vertical forms, planted in nature like blue crystals, symbols of the power and unity of Nations”(2).

“A square is not a crossroads”, Gutton explained. His insistence that the project be “tactfully inserted in nature” was warmly received in Geneva. He was celebrated as a “poet”: “It is a marriage between poetry – but also freedom – and logic,” wrote the Journal de Genève; “This garden is truly a garden.” As for the towers, the Genevans’ perpetual bogeyman: “Yesterday we discovered the poetry of glass […] a material as beautiful as marble […] It is like a dream. Will Geneva someday resemble what Mr. Gutton suggests?”(3)

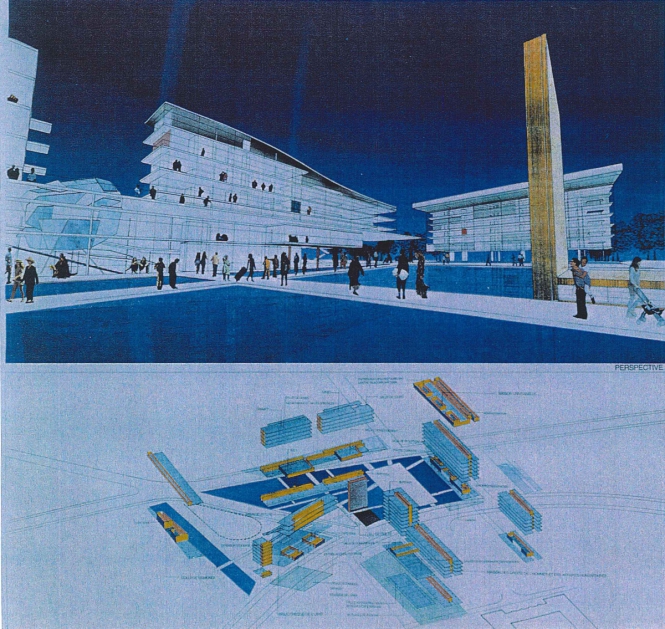

Massimiliano Fuksas's vision of the Place des Nations in 1995

© Département des Travaux Publics

The answer was no. Pressured to build housing, offices, and traffic corridors, the city tempered its ambition. It had neither the available space nor the funds to realize Gutton’s plan. Yet its memory still lingers today, like the ghost of what might have been, and indirectly inspired at least one building, as we shall see when discussing the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in Varembé.

In 1958, Gutton, still reeling from his success, wrote: “Foreigners arriving to Geneva from France and Ferney will be greeted by a sight worthy of the teachings of Voltaire and Rousseau.” In 1970, he resigned from his post as advisor to the city after a harassment campaign mounted by a narrow-minded civil servant who did not see the Place des Nations as a problem requiring an architectural solution (4).

And so, no solution was sought until the 1990s. The square was a no man’s land: the property of neither Geneva nor the international organization, engulfed by cars, hostile to pedestrians, but welcoming to the protestors who pitched their banners on its patchy lawn. It had become such an eyesore that, in 1994, the federal, cantonal, and city governments declared a solution must be found. The international organizations were asked for their input on one more architectural contest. The brief concerned the “public gathering place” of the Place des Nations and the development plan for the area extending from Pregny to the lake. Filled with sudden determination, the authorities positioned the redesigned square as the focal point of the future development of the entire right bank, including its parks.

The walking path (yellow) Fuksas drew from the Palais to the lake

© Département des Travaux Publics

First prize was awarded to the Italian architect Massimiliano Fuksas (5). His project surrounded the square with modern buildings for international organizations; an “equipped walkway” would lead from the square through the Rigot estate and Sécheron to the lake. Traffic was not only eased, as the city wanted, but openly encouraged. The plan was hotly debated in public consultations and modified as a result, but neighbourhood associations, environmentalists and heritage groups still called for a referendum. They warned of two threats: the “privatization” of the square and the “repeated concreting of Geneva’s parks”. In response, a committee called “For a Place de Nations that is open to the world” formed. The dispute pitted institutions, representing important economic interests, against civic groups with a social, environmental, or heritage agenda (6).

The row was characteristic of the time: the end of the Cold War had renewed the UN’s leeway, and its ability to become the main institution of global governance was viewed with optimism. These hopes were shared by a multitude of non-governmental organizations, which increasingly saw themselves as stakeholders in that governance. The Place des Nations became a rallying point and platform for greater visibility.

Fuksas wanted the square to reflect the prestige of the UN as an organization of states. His design conveyed this status through a series of basins, “mirrors crossed by walkways”. However, he failed to consider the square’s new virtual owners: activists from around the world who gathered there in large numbers to protest or make their views heard. The chair had already cast its vote. In this context, a large water feature was likely to be perceived as the equivalent of a “no loitering” sign.

On 7 June 1998, the city of Geneva held a referendum on the square; Fuksas’s proposal was rejected by a 52.4% majority.

The poor Place des Nations as it stood before its rehabilitation in 2007

© Alain Grandchamp / Documentation photographique Ville de Genève

In 2002 works for the new Place des Nations began in accordance to the groupe Orsol's plans

© Alain Grandchamp / Documentation photographique Ville de Genève

Finaly in 2007, the awaited Place des Nations promised by Geneva to the League of Nations in 1929 is achieved

© Alain Grandchamp / Documentation photographique Ville de Genève

It was a heartbreaking defeat for the project’s promoters. The meaning of the Place des Nations was as disputed as ever: a space between buildings? a park? a forum? André Gutton’s ideas had been abandoned, Fuksas’s rejected. Was there any hope left?

The city and canton went back to the drawing board. In September 1999, they submitted a simplified plan to the international organizations, civic groups, and local residents, who finally gave it the green light. A fourth competition was launched. In 2001, the Orsol Group presented its proposal, led by Christian Drevet, the Lyon-based architect and landscape designer who had re-imagined Lyon’s Place des Terreaux. Their plan nearly doubled the pedestrian portion of the square. Simple and uncluttered, with no construction along the perimeter, the space could be used in several ways: for recreation (thanks to the water jets and lights), as a public forum, or as a site for contemplation, on dark December days when the only thing worth protesting is the desolation of winter.

© Alain Grandchamp / Documentation photographique Ville de Genève

The town council noted all the objections. Some worried about energy use, others that the square resembled a landing strip. Some found it too austere, others too conservative. The granite paving was disputed. There were endless arguments over the cost. A supportive majority gradually coalesced. A motorists’ association lodged an appeal, and lost.

“It took Geneva more than half a century to finally give itself a Place des Nations worthy of its international role,” a city councillor declared when the square was inaugurated. The “square versus crossroads” dilemma was resolved through a decisive synthesis of the two: from now on, this was the “Crossroads of Nations”, the councillor added (7). Unfortunately, the cost of lighting and powering the water jets is so high that the square is more often than not “on standby” - a situation the UN has learned to live with.

© Alain Grandchamp / Documentation photographique Ville de Genève

(1) André Gutton, “Le concours international pour la Place des Nations, à Genève”, in La Vie urbaine, Paris, 1959, no. 2, pp. 80-110.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Journal de Genève, 8 November 1958.

(4) Andé Gutton, Conversations sur l’architecture, De la nuit à l’aurore, éditions Zodiaque, Paris 1985, vol.2, p. 457.

(5) Massimiliano Fuksas, “Une histoire d’eau, Aménagement de la Place des Nations”.

(6) Ola Söderstrom, Béatrice Manzoni, Suzanne Oguey “Lendemains d’échecs, Conduite de projets et aménagements d’espaces publics à Genève”.

(7) Christian Ferrazino in “Place des Nations, Genève”.