Chapter 4: Architectural Competitions: Imagining the City of Peace

This fourth article about the architecture of international organizations in Geneva examines the role of design competitions in the development of new architectural forms and building techniques. As of the 1960s, modernism had outgrown its early-twentieth-century timidity to become fully established. Le Corbusier’s protest over the rejection of his design for the Palace of Nations was instrumental in bringing about this change.

In 1878, while overseeing the restoration of the Cathedral of Lausanne, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc wrote a short fable called Histoire d’un hôtel de ville et d’une cathédrale (The Story of a Town Hall and a Cathedral), set in the imaginary town of Clusy. In one passage, he describes the rebuilding of a cathedral after a fire. The bishop, in his wisdom, decides to identify the most talented men through an architectural competition. A brief is drawn up based on the needs and preferences expressed by an assembly of users of the cathedral. A jury comprised of clergymen, townspeople, members of the professions, masons, sculptors, and carpenters is then appointed. One of the project’s central requirements is that it remain within budget. Three contestants are shortlisted. They are invited to present their project before the jury and encouraged to engage in discussions until the most sensible solution emerges.

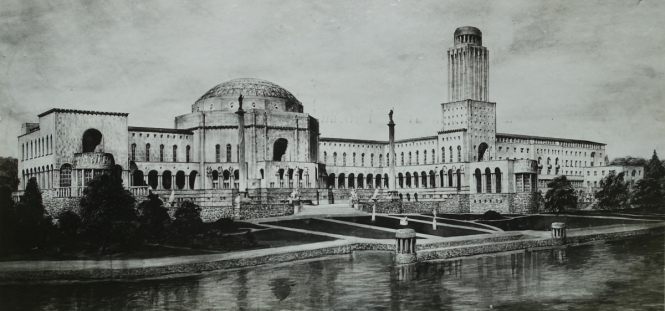

The initial location where the Palais had to be built, on the Moynier and Batholoni estates in Sécheron

© Histoire et architecture du Palais des Nations de Jean-Claude Pallas; 2001

For Viollet-le-Duc, the aim of an architectural contest was to deliver an outcome that satisfied everyone. To that end, all views and interests had to be taken into consideration, from the definition of the brief to the choice of the winning entry by a well-informed jury.(1) He saw architecture as a public good with both practical and spiritual aims. A building’s function was inseparable from the idea it represented.

“Palace” was the initial term used to describe the structures intended for the League of Nations in Geneva: a palace for labour and a palace for the Assembly of Nations. The common good was global. But was an architectural competition on that scale even realistic?

In 1922, the director of the International Labour Organization, Albert Thomas — anxious to get his new institution up and running, in its own premises — asked his council to hold a competition. Participation was limited to Swiss or Swiss-based architects. Only the jury would be international.

There were strict requirements: the building needed to accommodate 500 employees, with a maximum budget of 2.5 million Swiss francs (soon raised to 3 million), and to provide “the dignity fitting to an international institution […] by conserving, as much as possible, existing stands of trees, especially near the lake”.

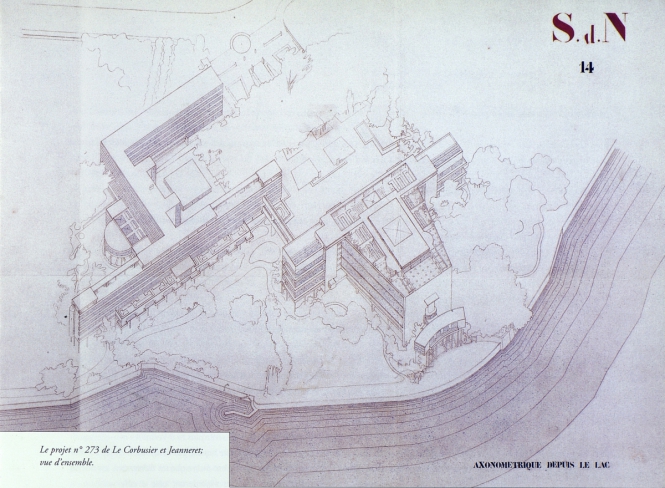

Project n°273 by Le Corbusier and Jeanneret, in the vanguard but controversial, awarded but put aside

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

Sixty-nine entries were received. The jury chose Georges Epitaux’s plan; an architect from the canton of Vaud, he was best known for shop buildings in Geneva and Lausanne. His building was inaugurated in 1926. A compromise between neoclassicism and functional modernism, it fit in with the dominant style in French-speaking Switzerland, which remained strongly influenced by the French Beaux-Arts tradition. Though disparaged in the trade press and criticized by the public, it was no more controversial than the Permanent Court of Justice in The Hague, a Neo-Renaissance structure built in 1905, also through a competition.

That same year, trouble of a different kind was brewing: the launch of a competition for the Palace of Nations, which would place Geneva squarely in the middle of the architectural debates of the day. The Palace was to be built next to the lake, on the Moynier and Bartholoni estates purchased by the League.

In 1924, the committee appointed by the Assembly of the League of Nations to manage the competition opted to make it “universal”, that is, open to architects from around the world, including countries that had not joined the League, such as Germany, the United States, and Russia. The process would certainly be difficult, but it was the price to pay to ensure the future palace was truly universal.

Reality moderated the committee members’ zeal. They decided to limit the competition to architects from the League of Nations’ 55 member states. In April 1926, the League published its brief: architects had to “combine all the essential organs necessary for [the League’s] operation in a practical and modern fashion” and reflect “the higher purpose of a monument intended to symbolize the peaceful glory of the twentieth century, through the purity of its style and the harmony of its lines”.(2)

The competition was hugely successful. In January 1927, crates of plans and models started to arrive at the Geneva offices rented by the League specifically to display them. There were so many entries, and they took up so much space, that an annex had to be built. In all, 377 proposals were received and numbered by order of arrival; the first came from Romania and the last from Australia. The cost so far was 800,000 francs.

A colossal amount of work was involved: thousands of technicians spent six months sorting through 10,000 blueprints, at a total expense of 4 million Swiss francs, for a Palace with an estimated budget of 13 million.

The jury had a comparable responsibility. After convening a total of 64 times, it reached a unanimous but difficult decision on 5 May 1927: none of the 377 projects was suitable. Despite a “remarkable wealth of ideas”, a “significant” number of entries “failed to sufficiently take into account the material conditions required by the brief”.

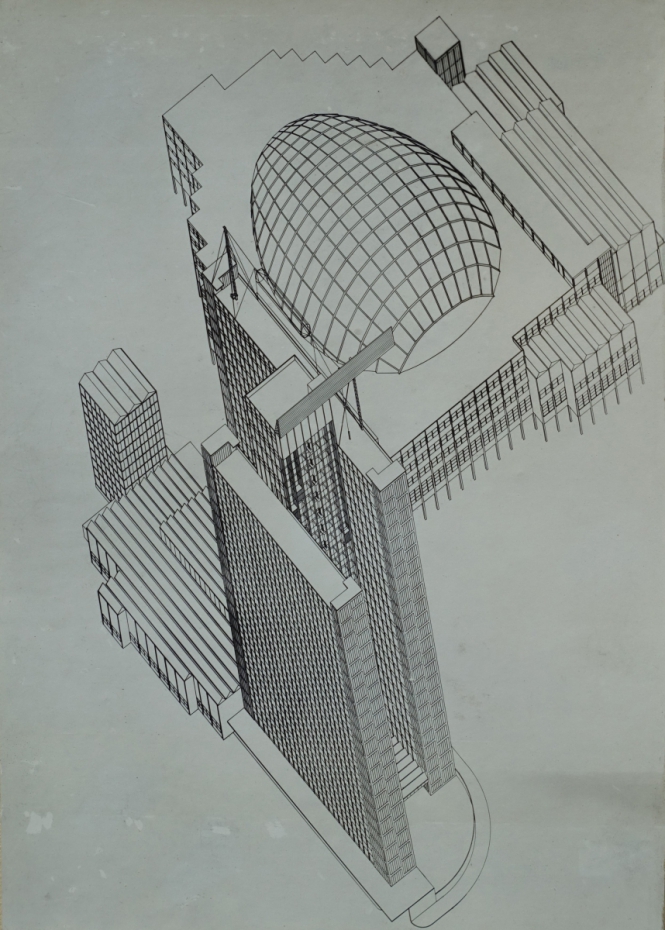

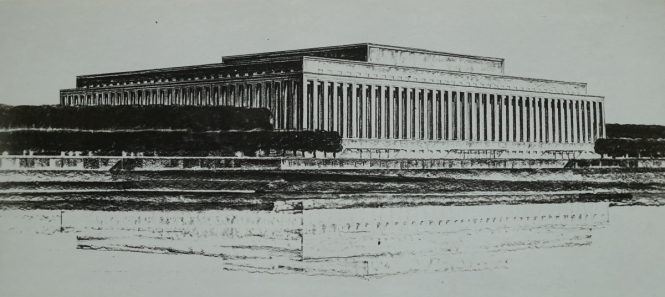

Also in the vanguard, the project of the Swiss architects Hannes Meyer (1889-1954) and Hans Wittwer (1894-1952), awarded one of the nine second prises

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

The jury, which had formed in 1924, included nine architects from nine countries “close to Geneva and famous for their architectural production”, namely Belgium, Austria, Great Britain, France, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, the Netherlands, and Sweden. The chair was Victor Horta, a Belgian star architect. The talented panel, representing various contemporary styles, explained its non-choice by the “radical divergences” between the entries “with regard to their understanding of the great task that was required”, a situation it ascribed to “the evolutionary phase in which contemporary architecture finds itself at present”.

As a result, the top nine prizes rewarded projects at opposite ends of the spectrum from both a technical and an aesthetic point of view. The project submitted by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret was strikingly modern, as was that of another pair of Swiss architects, Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer, who won second prize. Faced with the daunting challenge of creating a structure honouring an idea of the world, and with so many possibilities to choose from, the complex machine of the jury broke down, partly due to the differing cultural sensibilities of its members.

In his history of the Palace of Nations, Jean-Claude Pallas notes that the League emerged from a conference at the Palace of Versailles, the archetype of a classical representation of power. The European and international political elite who were commissioning the Palace of Nations were in no hurry to give up their acquired tastes. And the jury, avant-garde though it was, could hardly afford to ignore its patrons’ preferences.

Meanwhile, another protagonist was hiding in in the wings: the public opinion of Geneva. The League was free to do whatever it wanted with the land it had bought, in a city that had welcomed it knowingly, even proudly. But anxiety mounted as crates full of plans poured in, and rumours started to circulate about the participation of this or that “modern” architect. On 30 March 1927, the writer and art historian Daniel Baud-Bovy, sensing an impending disaster, wrote in the Journal de Genève: “May the [jury’s] choice temper the regret we feel as citizens of Geneva over the loss of those beautiful, half-rustic, half-urban estates, which garland the threshold of our city with their pastoral elegance.”

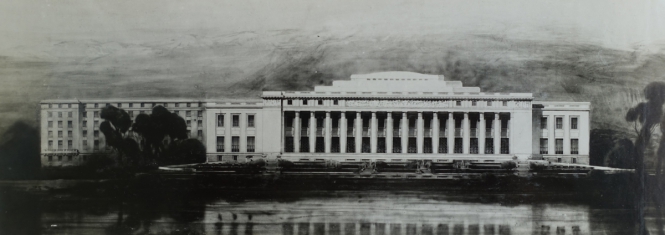

Henri Paul Nénot (1853-1934) and Julien Flegenheimer (1877-1947). Nénot was selected as head of the building of the Palais until he died.

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

In April, the newspapers’ editors made a different argument: “The Latin character of the shores of our lake is universally acknowledged […] A building in the Nordic or German style would be discordant.” The newspaper called on a Swiss member of the jury, Karl Moser, “an advanced Modernist of the German school”, to set aside his personal preferences and preserve “the fundamental beauty of the Lake Leman shoreline”. Karl Moser was an undisputed authority on architecture at the Zurich Polytechnic Institute, founded by the German architect Gottfried Semper, which architects in French-speaking Switzerland had long opposed.

It was not the first time that an architectural competition failed to produce a result. Buckling under its own symbolic weight, however, this one failed to achieve its central mission: to both serve a purpose and demonstrate an idea.

Le Corbusier turned the jury’s non-choice into a global scandal. The debates that ensued enabled him to popularize his position: to demonstrate the idea by serving the purpose. Necessity dictated all of Le Corbusier and Jeanneret’s formal choices: in an age of paper, windows were designed to slide against the facades to maximize light in the offices; the Secretariat was placed on stilts to ensure there were no damp, windowless rooms and to provide a clear view of the shimmering waters of lake from the top of the hill; the conference room walls were made of glass bricks to allow delegates to the Assembly, which met in the autumn, to enjoy the splendour of the season. Acoustics, circulation, lighting, ventilation: every formal element was designed to optimize a new way of life in an historically unprecedented institution.

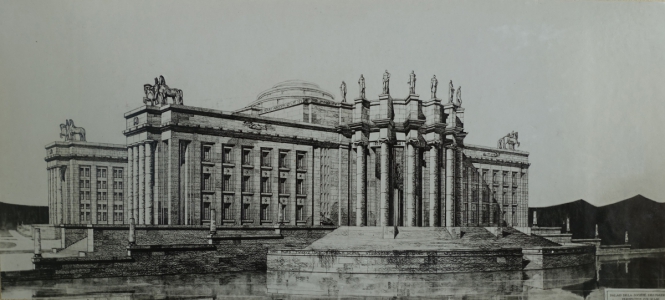

Carlo Broggi (1881-1968), Giuseppe Vacaro (1896-1970) and Luigi Franzi (1898-1971). Broggi succeeed Nénot as head of the building of the Palais

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

Though rewarded with a prize, their extreme functionalism was ultimately rejected. The ensuing disagreement “between the Academicians and the Moderns” echoed the dispute between Voltaire and Rousseau on the question of theatre in the Encyclopédie. For architectural historians, “the 1927 competition for the Palace of Nations remains a symbol of the crisis of judgement in the twentieth century”.(3)

Nonetheless, it provided the names of the five architects commissioned, between 1929 and 1936, to build the Palace of Nations on the larger Ariana plot, where it still stands today.

The competitions resumed after the Second World War, when the Palace of Nations became the European headquarters of the UN, alongside a string of new intergovernmental organizations, which were also seeking premises.

An international contest for the square in front of the Palace of Nations, or “Place des Nations” was held in 1956. The decision to build the Palace on the Ariana had created an unresolved urban planning dilemma: how to organize traffic in the new district, and around the square that had been promised in 1929. One hundred and twenty-three projects from around the world proposed solutions that provide the square with “a monumental aspect in keeping with its status as an international centre”.

First prize went to the French architect André Gutton, whose plan combined roads on two levels with a landscaped pedestrian area, enhanced and demarcated by three hexagonal towers. The jury applauded his “bold gesture” but felt that it did not fully meet its requirements. It even wondered whether it was possible to “integrate data that seem almost irreconcilable, as the outcome of the competition would tend to reveal”.(4) Geneva would have to wait another fifty years, and hold another competition, before the “data” of traffic and of monumental scale were finally reconciled.

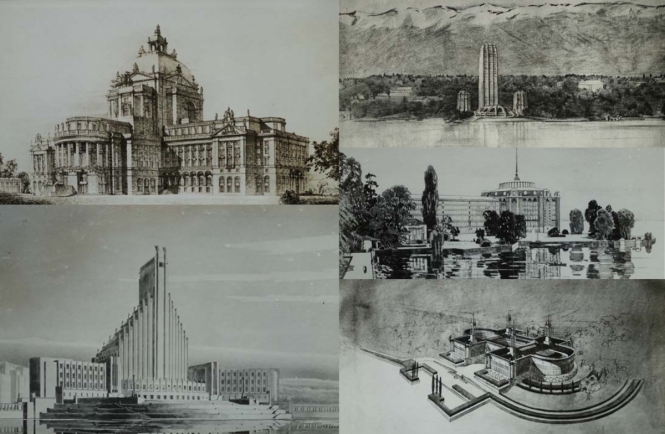

Jozsef Vago, Hongary (1877-1947), one of the nine first prizes. He will participate to the final construction of the Palais.

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

A more widely publicized competition was held in 1960, for the new headquarters of the World Health Organization. Though global, it was limited to fifteen invited architects. And this time, it produced a winner: the Swiss architect Jean Tschumi, renowned for the headquarters of Nestlé in Vevey, unveiled a few months earlier. Described by the Neue Zürcher Zeitung as a “one-man architecture biennale”, Tschumi also curated architectural exhibitions, gave speeches, wrote newspaper articles, and hosted architectural debates.

The battle for modernity had been won. Now, the challenge was to recognize its potential and its effects.

Proposed designs for the WHO elicited both interest and concern. “The context of post-war architecture is characterized by the popularization and acceptance of modern architecture, and by the emergence of a wide range of individual voices and styles”, write Isabelle Charolais and Bruno Marchand.(5) However, despite the various contemporary styles represented, this competition had only minimal influence on local architectural production, the authors observe. This was perhaps because some of the most famous names in modern architecture at the time did not take part –– Alvar Aalto and Walter Gropius, for instance, who had been considered as jury members but ultimately not invited. Their absence no doubt limited the competition’s potential ripple effects.

In 1966, when the ILO started planning its new headquarters, it was those famous names it had in mind –– the likes of Niemeyer, Sert, Tange, and Pei. They would provide oversight, and the ILO, to save costs and increase efficiency, would hire architects to carry out the project.(6) In the end, the panel members were less famous, but still highly effective.

Erich zu Putlitz, Germany (1892-1945) one of the nine first awards

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

For most international organizations built in Geneva after the war, holding a design competition became common practice despite the cost, difficulties, drawbacks, and occasional intrigues involved. The stakes are now lower, however: eclecticism is accepted and originality less controversial. Form largely depends on a set of strict requirements regarding energy use and environmental considerations, which significantly curtail architects’ creative freedom. In their promotional documents, competitions tend to emphasize the technical ingenuity needed to conform to current environmental standards.

Yet the secret member of the 1926 jury — public opinion — remains. It worries about trees and the “environmental footprint”. It still views construction with suspicion. But what does the public know about the gesture of designing a building? There never was a second edition of the wildly popular “Architecture Biennale”, organized in 1960 on the occasion of the WHO competition. There exists in French-speaking Switzerland no institutional or media platform designed to influence tastes or foster greater public understanding of architecture. Competitions remain dominated by experts, even if juries sometimes include representatives of user groups. The public has lost interest.

In Lectures on Architecture, Viollet-le-Duc encourages architects to teach “amateurs”, as “it is only by coming into contact with artists that they may develop good taste”. Writers, filmmakers, and painters have their place in the media; they are visible, and their views on their own work are heard. Why aren’t architects?

Friedrich Hess (top left); below D.Roosenburg; Richard Scharff (top right); Hans Bernoulli (centre) and Alexander v. Senger

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

(1) Quoted by Armand Brulhart, “L’institution du concours”, in Concours d’architecture et d’urbanisme en Suisse romande, Lausanne, Payot 1995, pp. 37-47.

(2) Factual information about this competition are based on Histoire et Architecture du Palais des Nations (1924-2001) by Jean-Claude Pallas, United Nations, Geneva, 2000.

(3) Jean-Pierre Chupin, Carmela Cucuzzela, and Bechara Helal in “Architecture competitions and the Production of Culture”, Quality and Knowledge, Potential Architecture books, Quebec, 2015.

(4) “Concours d’idées pour l’aménagement de la Place des Nations à Genève, Conclusions du jury”, in BTSR no. 16, August 1957.

(5) “L’éclatement des tendances : les concours genevois de l’après-guerre”, in Concours d’architecture et d’urbanisme en Suisse romande, Lausanne, Payot, 1995, pp. 96-110.

(6) Le siège de l’OIT à Genève, étude patrimoniale, Franz Graf, Giulia Marino, EPFL.